Means of progression – Meaning of progress

Als we het hebben over de vormen van onderzoek die relevant zijn in het hoger kunstonderwijs, kunnen we metaforisch verschillende manieren van voortgang gebruiken. In dat opzicht springt voor Bert Willems vooral de rupsband eruit. Hoe kan de rupsband inzichten verschaffen in de manier waarop we naar vooruitgang kijken en erover denken? We eindigen met de suggestie dat de kunstschool een goede omgeving is voor artistieke onderzoekers als gelukkige, kritische, maar niettemin indringende verkenners van de werkelijkheid.

Discussing the forms of research that are relevant in higher art education, we can metaphorically use various means of progression. In that respect, the caterpillar track in particular stands out for Bert Willems. How can the caterpillar track provide insights into the way we look at and think about progress? We end up with the suggestion that the art school is a good environment for artistic researchers as happy, critical, but nonetheless intrusive explorers of reality.

This is the true story of the academic career of the caterpillar track. At first sight, it may be a strange story. Even the caterpillar track wasn’t sure why it would start this academic adventure. Why this kind of career? Isn’t the caterpillar track only useful as a worker in the field? What is the advantage of the caterpillar track in the academic world? Why would academics choose caterpillar tracks? Despite this strangeness, the caterpillar track just started its academic career, against all odds, and that is why we can tell this story. So, let’s dig in.

To frame this adventure of the caterpillar track, let’s compare it with the successful story of the wheel. The invention of the wheel – surely everyone knows it from history classes – that important invention, that event that set everything rolling. Exactly where and when it happened is not clear, but the wheel may have been invented as a turntable for ceramic work or for transferring water from the lower rivers to the higher fertile land. But the main reason for its existence is for the transport of goods and people. This made the wheel an important stimulus for technological, economic, and social development. So much for the standard story…

Because the invention of the wheel is so associated with the idea of progress and development, I would like to compare it with the invention of that other ‘means of progression’, that of the caterpillar track. This invention is of a more recent date and in contrast to the invention of the wheel, there are many more historical sources that describe exactly how and where this happened (see for example the pioneering work of Sueter in 1941).1 The first developments started in the agricultural context (with the first concrete ideas showing up in the nineteenth century) but as is so often the case with technological developments, pressure from the military played a major role: tanks, with their caterpillar tracks, played an important role at the end of the First World War and subsequently formed the basis of Hitler’s Blitzkrieg during the Second World War. Since these developments, caterpillar tracks showed up as a relevant and commercially attractive alternative to the wheels in the fields of agriculture, road construction, and mining. Yet the attention paid to the invention of the caterpillar track is significantly lower than that of the invention of the wheel. Why is one invention in the top-ten of best inventions of all times whereas the other is not? Is this difference in attention only because one invention happened before the other? In what way do these two means of progression shed a different light on what we call progress and development?

Phenomenology of the caterpillar track

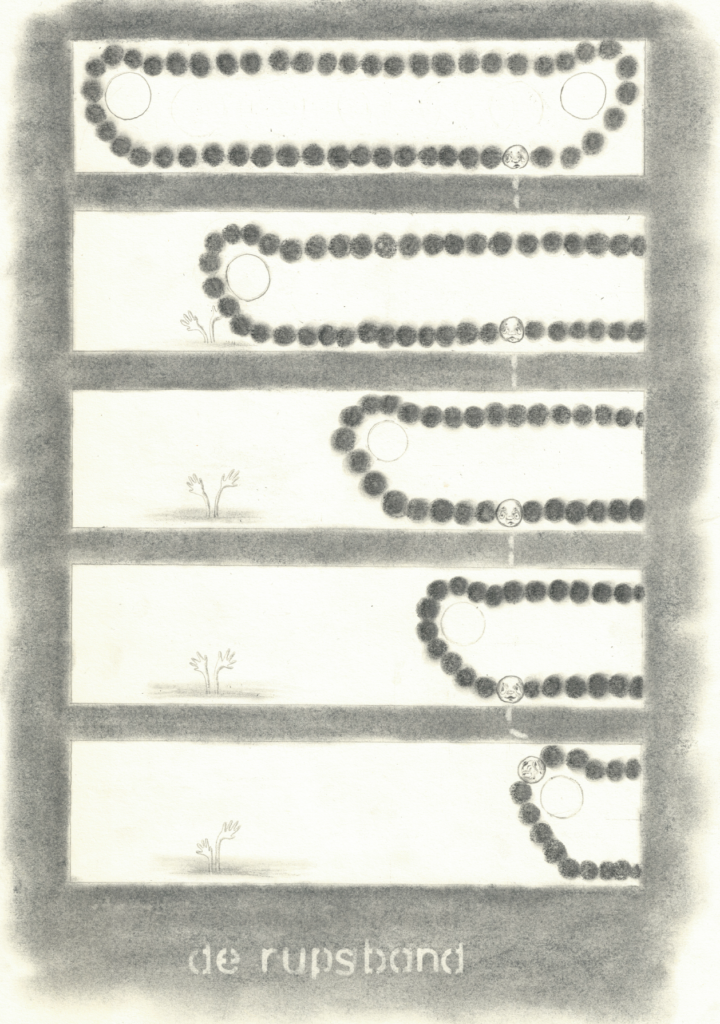

All my life I’ve had a profound fascination with caterpillar tracks: grapples, tanks, snowplows, bulldozers… I loved to see them pass by. Moved to tears when I could spot one. What intrigued me was not just the overwhelming, powerful appearance of these machines (although that surely affected me as a young boy), but also their peculiar way of moving. How different this mode of locomotion is when you compare it to the progression of the wheel. At first sight, you think the caterpillar track is just another variation of the wheel, as it makes a circular – or rather elliptic – motion during the whole progression. However, when paying close attention to the ground you start noticing the strangeness of its movement. While the vehicle is moving forward, the lower part of the caterpillar track is completely fixed to the ground, ‘touched down’. It does not move at all! At the same time the upper part of the caterpillar track is moving, and this at a very high speed, even faster than the vehicle itself. And all of this (both the stationary lower part and the fast-moving upper part of the caterpillar track) is happening while the vehicle is heading forward in a continuous movement.

Imagine you are a point on this caterpillar track. You are lying fixed in the mud, being in touch with the ground, along with the other neighbouring points. When this work in stationary modus is completed, a series of rapid forces is imposed on you: you are lifted out of the mud, you are moved to the front of the vehicle, and you are pushed back into the mud. Once this short period of rapid successive motions is over, the heavy work of pulling the vehicle can start over again, fixated on that very spot. The continuous movement of the vehicle is translated into a discontinuous movement of you, as a point on that caterpillar track. In other words, a combination of complex forces on the caterpillar track are supporting linear continuous movement of the vehicle. This close, focused, and intense engagement with the soil characterizes the caterpillar track. Now when you imagine yourself as a point on a wheel, it immediately feels very differently. How nice and smooth this motion is! You are part of a beautiful continuous movement, without jerks or bumps. And, as an individual point, you hardly come into contact with that dirty ground. And in that very precise moment that you do touch the ground, it is in complete isolation. Moreover, the wheel-driven vehicle seems to float above the ground, keeping enough distance from the underlying surface.

The underground

When we inspect the surfaces used by the wheel, mostly we see an underground that does not provoke any resistance. Exemplary is the progression of the cyclist, who makes use of a wheel which, in its most inflated state, comes closest to the perfect geometric circle. And even when there are cycle paths, cyclists still prefer the road, to avoid even the smallest irregularity. The cyclist tends to use those road sections that allow the wheel to ‘run smoothly’ and do not give rise to any discontinuity in progression. Thus, we notice that the wheel prefers those parts of the world that have been ‘prepared’ in some way. How different this is compared to the progression of the caterpillar track. No well-trodden or pre-structured paths are preferred, on the contrary – there’s the realistic risk of breaking those paved roads apart when turning the vehicle. Caterpillar tracks are preferably used on ground surfaces that cannot be predicted, that are irregular and provoke resistance. Here’s the big difference between the caterpillar track and the wheel: the ground is not adapted to (or prepared for) this means of progression!

What do we mean when we say everything is running smoothly? This indicates a certain attitude towards what is coming our way: the biggest problems have been solved, only the details have to be cleared, everything happens automatically, we don’t have to worry, we move forward without knowing it, and when problems do arise, they will be solved on the basis of all scientific and technological knowledge that is (or will be) available to us, as long as we stay on the pre-structured paths and we don’t do crazy or wild things. Isn’t this an adequate description of the prototypical idea of progress (traces of which can be found in our current Western society)? But sometimes things don’t run smoothly. Sometimes circumstances force us into unpaved terrains: for example, a virus threatens global health, or an ever-increasing mass of people has no prospect of any form of dignified life, or nature does not appear to be an inexhaustible source to exploit and starts to react to our human activities, etc. What can we learn from the wheel and caterpillar track when we care about what is coming towards us? What is the meaning of progress in the light of these two means of progression?

Means of progress(ion)

Some means of progression, such as the wheel, prefer to use a prepared surface. Can we say the same about some ‘means of progress’? Are there ‘means of progress’ that make use of a prepared surface? The old Greeks regarded mathematics as a separate discipline, separate from nature (or Physis as they called it). For them, mathematics was only applicable in the abstract realm, having nothing to do with the concrete natural processes that could be observed. But since, amongst others, Galilei, Copernicus, and Kepler projected mathematics into nature (undoubtedly a great step forward for the sciences) our mathematical, analytical view of reality has become increasingly dominant.2 For these early scientists, mathematics was the ideal way to transcend individual opinions (Doxa), and mathematics has had a firm grip on science ever since. Reality is neatly prepared into analyzable units before it can be systematically ‘experienced’ or should we say ‘measured’. In this tradition, our ‘vehicles’ of knowledge keep their wheels at a safe, objective distance to the ground, anxiously obscuring that there is always one point of contact. These vehicles appear to be as light as a feather – enlightened.

This tactical preparation of the underground was of course not limited to the natural sciences. Some disciplines within the humanities (for example, psychology and sociology) also adopted these analytical glasses for observing reality. And finally, based upon this specific preparation of the underground, one could think of the best ways to arrive at real knowledge: because of this analyzable, pre-structured categorization, it was possible to develop research methodologies that resulted in the most optimal ways of acquiring knowledge. This methodological development also took on an increasingly compelling, normative character: objectivity, reproducibility, representativeness, validity, etc. And based on this systematic preparation of the underground, science became a super-efficient modern ‘means of progress’ that had a significant impact on the technological, economic, and social development. So much, again, for the standard story…

Unprepared reality

But how do we deal with those parts of reality that are unknown to us? What about those parts of reality that are of interest to us in unprepared conditions or that even do not allow for preparations? What happens to those parts of reality that can only be explored by entering into a deep, personal, and subjective relationship with them? Aren’t we missing something by using only the wheel as a metaphor for progress (‘running smoothly over prepared undergrounds’)? Here perhaps the caterpillar track can come into play, as it cannot but enter into a profound relationship with the subsoil instead of making it into an instrumental object from a detached position: the tracked vehicle’s being-in-the-mud allows it to go along, without a forced and abstract detachment from the underground. The track adapts to the surface: progress – or better: ‘moving along’ – can be made regardless of pre-existing quantitative (i.e., metric) or qualitative (i.e., pre-conceptualized) frames of reference. And, in this way, it is possible to look for the uniqueness in the phenomena instead of eliminating them by putting them in pre-conceptualized categories or making them measurable in advance (to have control over the ‘experimental’ or constructed situation). This also allows for a great deal of freedom regarding the way in which reality is dealt with methodologically: ‘being empathic with the situation’ rather than ‘having control over the situation’. Consequently, more interactive, bodily, and therefore less distant forms of knowledge are also available for researchers. It is time to further explore these means of progress (‘caterpillar methodologies’) in the academic context, in addition to the standard methodologies.

We can argue about when exactly the end of modernity took place, but if we don’t look at it in too much detail, it pretty much coincides with the emergence of the caterpillar track as a means of progression. Within the humanities, and more in particular with the appearance of phenomenology, existentialism and post-structuralism (after, and maybe due to, the devastating impact of the second World War), the conceptual space was created for other views upon reality, views that tried to avoid pre-conceptualizations of those phenomena one wants to study (e.g., grounded theory). The standard ideas about progress (‘running smoothly’) were questioned together with the classical dichotomies within the sciences: subject vs. object, culture vs. nature, mind vs. body. As you can see, the caterpillar started its academic career decades ago. How can we further explore these ‘caterpillar methodologies’ in our current academic context?

The academic career of the caterpillar track

However, before we move on, we must be careful. There are also some disadvantages associated with the metaphor of the caterpillar track when it comes to dealing with reality. In fact, after the track has passed through, the surface usually does not emerge unscathed. The trail of destruction left behind by the tracks – not to mention the destructive function of most vehicles that use them – is obviously not what we mean by ‘moving along with reality’. So, in that respect a nice flat wheel is to be preferred. Of course, it is for a caterpillar track simply impossible not to have an impact on the ground if you maintain such a deep and personal relation to it. And, as discussed before, sometimes this is the only way into these specific regions. Maybe we can imagine caterpillar tracks that are used by vehicles which have a genuine interest in the subsoil and do not plow through it in a very violent way? Maybe these kinds of gentle, curious but nonetheless intrusive caterpillar vehicles can be found in the research departments of art academies and conservatories? Maybe the art school is the perfect environment for the artistic researchers using caterpillar track-methods?

Why is the wheel in the top-ten of best inventions of all times whereas the caterpillar track is not? Is this difference in attention only because one invention happened before the other?

With these artistic researchers in mind, we can explore yet another distinction by using this metaphor of the caterpillar track. On the one hand, we see tracked vehicles that merely prepare the way for the wheel: creativity that is deployed in an instrumental way and that transforms the unexplored terrain into a controllable and therefore exploitable object: wheels transporting caterpillar tracks to unpaved terrains to clear things out (in a ‘master-slave-relationship’). Telling examples of this vision are amongst others: artists involved in ‘brainstorms’, artists stimulating economic innovation, or artists involved as illustrators, in service of ‘decent’ scientific research. On the other hand, I personally prefer tracked vehicles that are not in the service of instrumentalizing rough terrains, but that act as a grounded version of the wheel, thereby entering an impactful and meaningful – sustainable – relationship with these unexplored terrains without the need to upgrade them. In this sense, the use of the caterpillar track in service of the wheel should be distinguished from the more positive use of the caterpillar track as an adventurous, happy but also critical explorer of reality. It is especially according to this second interpretation of tracked vehicles that artistic research has added value within the academic world.

This is not an essay against science. No, not at all. On the contrary, I love science and all the good things it brings us. It is just that this cannot be the only way to deal with, or better move along with reality. Science is all too much based on a prepared reality to get to know this reality, creating an objective distance with it, a distance that can be harmful at times. So, in addition to this need for control over reality we can explore other methods of moving along with reality. And here our artistic caterpillar tracks show up, starting off their academic careers. I like to see artistic researchers, regarded as those that move in between research and an artistic practice that is bound to life itself, as the new caterpillar tracks of this world, not just working to make life easier for us, paving the way for wheels to take over, but rather to explore new ways of understanding and of being. In my view, artistic research is grounded in an experienced – lived – reality, where the methods used are not limited to objective viewpoints from out of nowhere (‘the point of Archimedes’). This is the true story of the academic career of the caterpillar track!

[1] Sueter, Murray F. The Evolution of the Tank: A Record of the Royal Naval Air Service Caterpillar Experiments. Hutchinson, 1941.

[2] Husserl, Edmund. De Crisis Van De Europese Wetenschappen En De Transcendentale Fenomenologie. Boom, 2018.

Bert Willems

is Head of Research at PXL-MAD, School of Arts, Hasselt, and Professor at Hasselt University (Faculty of Architecture and Arts). His main concern within these two institutes is the development of the research policy with a focus upon research in the arts.

Contact: bert.willems@pxl.be

This essay was originally published in FORUM+, an international peer-reviewed journal for research in the arts. The article’s DOI can be found here.